“Textiles embody all the dimensions of art: color, innovation, talent.” Stanley Marcus

Oaxaca Day Five: Our first stop today was a “Holy Crap Moment,” the 2,000-year-old Montezuma cypress tree, known as the El Árbol del Tule, which is one of the oldest, largest, and widest trees in the world Its gnarled trunk and branches are filled with shapes that have been given names such as “the elephant,” “the pineapple” and even one called “Carlos Salinas’ ears.”

This amazing gift from Mother Earth is located in the town plaza of Santa María del Tule. The tree is humongous!

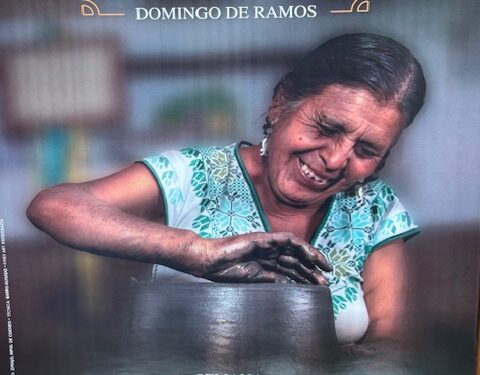

We then drove back to the weaving town of Teotitlán del Valle, its artisans rich in the tradition of handmade, finely crafted textiles. Many of the fabrics and garments are created using natural resources. The bright colors are attained by the use of natural dyes that culminate to create a vivid spectrum of indigenous colors and patterns.

There we were treated to a full demonstration: of wool separation, selection of natural dyes and spinning the wool into balls of threads, to the weaving of different patterns and styles. What made this demonstration more special than any previous one……was the weaver’s one-year-old son entertaining himself rolling a lime on the floor……I soon diverted my attention from her presentation and started rolling the lime with my newfound friend. And to think that in just 4 short years this child will start learning the family’s centuries-old craft. We know this because we were shown the life-sized loom that children play with.

Our next stop – the Sunday open-air market (or tianguis) at Tlacolula. It’s one of the oldest, continuous markets in Mesoamerica and the largest and busiest in the Central Valley region of Oaxaca. Locals and people from the rural, mountainous areas come to buy, sell and socialize throughout the entire day.

This market is on a triple dose of steroids; it makes all of the other markets I have visited in my travels mere lemonade stands.

Each Sunday, very early in the morning, officials close the main street for eight blocks. The number of vendors on any given Sunday varies but the number usually exceeds 1,000. The main market building is covered in a haze of smoke from all the grills down the middle of the narrow aisles of the poultry, pork and beef sections… this market gives off gives a new meaning to you buy it – we cook it and here is how it works . . .

Purchase your beef, pork, chicken, green onions, nopales and you’re 🌶… take them over to one of the grills where they will cook and roast your items. Then you find a tortilla maker and the agua fresca ladies, collect your grill items, go sit at a table and douse your items with fresh homemade salsa from the salsa lady. Realize that you have just employed over half a dozen indigenous women. The smells waffling through the markets…………made me ask myself how committed a vegetarian are you?!

I slipped for a quick second in order to experience a new taste sensation ~ chapulines or crickets – crunchy, chili, and lemony tasting. You wrap them in a tortilla with salsa and avocados and you’ll think that you are eating chicharrones (crackling pork skins).

I came to this market with a mission in search of a clay cazuela to cook with and some homemade black mole to bring home and churros for instant gratification … mission accomplished.

Most of the rural people who come to town on Sunday are indigenous and seeing the women dressed in their colorful traditional garb, such as rebozos, embroidered blouses, and wool skirts. Many of the indigenous women’s home villages can be identified by their clothing.

As you thread yourself through this colorful river of humanity, your ears hear a symphony of foreign sounds, native dialects of Zapotec and Mixtec, rounding up an already over-the-top multi-sensory experience.

There is a place to escape this madness – the Church of “La Asunción de Nuestra Señora.” It was founded as a Dominican mission in the mid-16th century, the retablos are adorned with silver and the doors have ornate ironwork. In the “coro alto” (rear gallery) stands a large baroque pipe organ. Mass was in session so we sat on one of the sides naves and sat quietly to soak up the reverence.

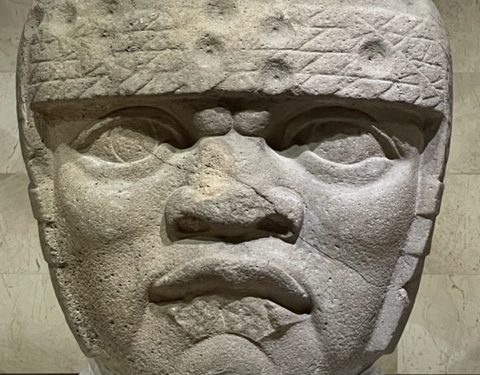

Our next stop: Mitla … or what I’m calling the “lace stone palaces,” …a place that actually managed to survive the Spaniards’ ignorance and their destruction of anything that was considered of beauty by the people of the new world.

Mitla is the second most important archeological site in the state of Oaxaca and the most important of the Zapotec culture. While Monte Albán was the political center, Mitla was the religious center. The name Mitla in Nahuatl means the place of the dead or underworld. What makes Mitla unique among Mesoamerican sites is the elaborate and intricate mosaic and geometric designs that cover tombs, panels, friezes, and even entire walls. That it still stands is amazing.

The geometric designs that profusely adorn the walls of both the Church and Columns called grecas in Spanish are made from thousands of cut, polished stones that are fitted together without mortar. The pieces were set against a stucco background and painted red at one time. The elaborate mosaics are considered to be a type of “Baroque” design as they are elaborate and intricate and in some cases cover entire walls. None of these fretwork designs are repeated exactly anywhere in the complex and is unique in all of Mesoamerica.

As we walked through Mitla you could not get far from the geometrical patterns carved all around you. Our guide talked us into entering one of the old tombs … I had to crawl on all fours to enter what the ancients considered the underworld, the space was tiny and extremely hot….. which proves that hell is not for tall people.

We were not done yet ~ we still had one more stop ~ the town of Tlacochahuaya. The town was founded by a Zapotec warrior by the name of Cochicahuala, which means “he who fights by night.”

We visited its main church … the Templo de San Jerónimo, which was built along with a monastery at the end of the 16th century. It has notable altarpieces (retablos) and an organ that dates from colonial times. All the decorations and painted frescos were created by indigenous people using natural dyes and also inserting subliminal references to their gods, something the Spaniards missed in their zealousness – the symbols were discovered during renovations to its frescos.

Exhausted, we crashed upon returning to our hotel.